Flexibility can be a tender subject

Originally published in South Coast Today.

Long before everyone’s favorite sixth-round draft pick popularized the term muscle pliability, the sports medicine community championed the concept of muscle quality — be it tone, tension, resiliency or any other designation.

Many a massage therapist has bemoaned their clients’ tight muscles. I myself once got kicked out of a physical therapy clinic for being dehydrated. I was told that my muscles felt like beef jerky and was ordered to go home and drink water for a few days before returning for treatment. A resting muscle should have the feel of an uncooked steak, not a well-done steak, and certainly not a piece of beef jerky.

Tight muscles and/or flaccid muscles are just part of the overall picture when talking about the F-word: flexibility.

There are different categories of flexibility, but the one that we’ve all come to know and lose is a joint’s range of motion. My go-to example of above-average flexibility is a contortionist, whereas Oz’s Tin Man demonstrates poor flexibility (and no heart). There are thin people who look the part of a limber person who are in fact inflexible. There are also large seemingly immobile people who possess great flexibility. A given person may have above-average flexibility in certain joint areas, but below-average flexibility in others.

Like other areas of fitness, flexibility is largely influenced by genetics. Muscle, tendons, other connective tissues, and even skin provide resistance that limits range of motion.

In the past it was suggested that lack of flexibility was the cause of all orthopedic injuries and that flexibility training was the solution. There are many causes and contributors to orthopedic injury, flexibility being just one of them.

Lack of flexibility can be a problem, but too much flexibility can also be a problem. Both ends of the spectrum set the stage for a host of potential issues from altered joint mechanics to tissue breakdown.

Tightness correlates to a lack of shock absorption. Tight muscles can pull on other components of the joint structure in an unfavorable way, causing a chain reaction of assorted irritations and worse. On the other hand, joints that are too loose tend to be surrounded by muscles that have to work harder. The result is often compensatory injuries and overuse syndromes.

There are instruments that are used to measure joint flexibility and there are less precise tests such as trying to touch one’s toes. Besides range of motion itself, how a muscle feels is also something to consider. Tense muscles pulling on tendons when you’re squatting 300 pounds is normal, but tight muscles pulling on tendons when you’re sitting around watching TV might get you a trip to the trainer’s room.

When we think in terms of flexibility training, we often think of static stretching, holding a stretched position in a relaxed state. During physical activity our muscles are constantly being lengthened and shortened so, technically, stretching takes place all the time. But calculated static stretching can more strategically address flexibility. Stretching exercises aim to capitalize on the elasticity of a muscle and its accompanying soft tissues. A relaxed muscle will better yield to a stretch than a tight, contracted muscle that in effect fights being stretched.

This is one of the advantages of stereotyped yoga-style stretching, though dynamic stretching that uses sport-specific movements is useful for different reasons.

Stretching has its share of limitations, and so other methods are also in order.

When you have tight muscles that need loosening but stretching won’t do the job, think of your muscles as a slab of meat that needs tenderizing. Just as a chef uses a meat hammer, I’ve seen physical therapists who use their hands, elbows or whatever they can dig in there to loosen a tight muscle. Many runners use a product that is a modified rolling pin that allows them to work on their own leg muscles.

Like kneading dough or tenderizing a piece of meat, a tight muscle may sometimes require a hands-on, direct approach to loosening.

So what’s the so-called “right” amount of flexibility? Take the Goldilocks approach for this one. Not too tight, not too loose, ahhh just right.

Think in terms of your own individual needs as applied to positional flexibility. Gymnasts need to do splits, ice-hockey goalies typically drop to the butterfly position, and swimmers need to assume a streamlined position.

Don’t gauge your flexibility by whether or not you can put your foot behind your head. Flexibility should more importantly be a function of those body movements and positions that are relevant to your sport, occupation, hobbies and individual needs.

This isn’t to say that people shouldn’t aspire to greater levels than basic needs. But don’t leave the Russian ballet or a Bruce Lee movie thinking that stuff is normal, appropriate for you, or even good for you.

As long as you can comfortably realize those positions that apply to you and your world, and you don’t have tight muscles causing joint dysfunction, you’re probably about where you should be.

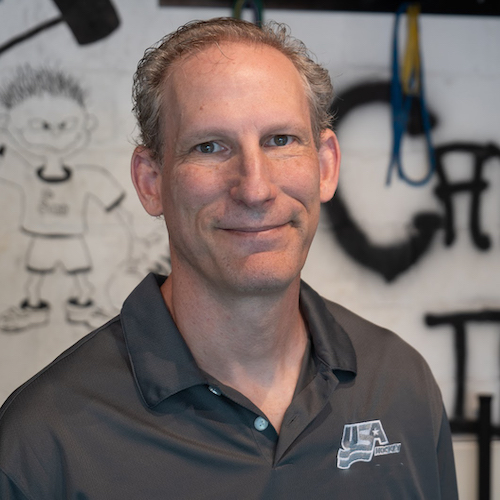

Norm Meltzer aka The Muscle-less Wonder