‘We have met the enemy, and he is us’ — Pogo

Originally published in South Coast Today.

Calorie has become quite the pejorative word. We try to avoid them and get rid of them. A calorie is neither good nor bad; it’s merely a unit of energy. So why do they enjoy such a bad reputation unlike a joule or an electron volt? Guilt by association!

The potential energy of food is expressed in calories. We require this energy for basic body function as well as for life’s activity requirements. We stockpile energy and we expend energy.

Supply and demand is the issue that seems to be such a plague on our society. When we are over budget with our energy utilization, we lose weight; when we are under budget, we gain weight.

Part of having units, such as calories, is to have a standard way of measuring something. But aren’t units also something to help us put things into perspective?

When someone goes on a 5 mile run, we offer them some hollow words of encouragement and maybe think better you than me. But if someone mentions they’re going on a 316,800 inch run, we think what the hell are you talking about?

It’s the same distance in both cases, but one we understand, while the other is difficult to interpret. As it may be, calories are difficult to put into perspective.

If only a tennis match was expressed in energy needs and translated to two eggs, a banana, and quarter cup of almonds.

People who struggle with their weight are like fuel-efficient cars, and lean people are like gas guzzling SUV’s. You may ask, how the ponderous husky people can be the typically smaller vehicles and vice versa? Chalk it up to irony and my poor grasp of analogy usage.

Overweight people are good at storing fat and conserving fuel (calories) like the fuel-efficient cars, whereas thin, fidgety people burn a lot of fuel (calories) like the poor-gas-mileage SUV’s.

It’s not inherently better to be one or the other, but rather a matter of situation and environment. It’s good to be short if you need some legroom on an airplane, but it’s bad to be short if you want to get on all the rides at the amusement park.

In the here and now, with the food availability, desk jobs, and fitness-reducing conveniences, it’s good to be a human, gas-guzzler. But if you’re floating around the ocean on a life raft, talking to volleyballs, it’s better to be a slow-metabolism, fat guy.

Despite the increasing problem of obesity, the body does a pretty good job of self-regulating energy balance. Amidst all of this unwanted weight gain, people are very skeptical about the idea that the human body is somehow good at keeping things in check.

Consider that long-term weight gain is a somewhat gradual process and then just do the math. Even in cases of substantial weight gain, the body is only off by a little bit on average per day. The problem is that a small amount of disharmony can collectively have a major impact.

Caloric needs vary between people, and there are practitioners who forecast those individual needs. Regulating caloric intake to match a specific calorie budget is not quantitatively difficult.

Between calorie charts, food labels, and all of the available measuring apparatus, you have everything you need. However, a food manufacturer’s suggested serving size, an appropriate serving size, and how much we eat don’t always match up.

When you buy an oversized muffin from the bakery, they know you’re going to eat the whole thing, and you know you’re going to eat the whole thing, but some of the people who assign caloric value might base their numbers on you eating only half of the offending muffin. Be suspicious of all foods and all people.

Obsessive-compulsive types might welcome such a chore, but most people don’t feel like quantifying food intake into energy equivalents. It’s not necessarily difficult, but who wants to read, measure, and do math with every moment of food consumption?

When it’s a short-term exercise to help become a mindful eater … sure, why not? But as a way of life, I’d rather die young and leave a not-so-beautiful corpse.

Measuring and pre-portioning your food has the same shortcomings as every other diet in the world. When you stop doing it, there’s a good chance you’re right back where you started.

Many nutritionists prefer food rationing through rough measurements like a handful of grapes or a serving of chicken no bigger than your palm. This method seems a bit more practical than toting around a food scale.

There’s no shortage of diets out there for our disappointment pleasure. They all claim to have figured out the solution to our collective weight problem. They market their competing theories on where we’ve gone wrong and offer up their specialized countermeasures. They all seem to work in the short-term, but the long-term success stories are harder to come by.

The problem with most diets is that they can’t be maintained permanently. When we revert back to the banned food choices, we nullify most of our gains. We seem to be accepting of intense short-term deprivation more so than long-term moderate change. People are willing to give it up for Lent but not scale it down for life.

When we eat, it behooves us to consider both calories and the characteristics of the food choices that provide those calories. Maybe not per meal or snack, but within the context of our overall diet.

Many success stories from the National Weight Control Registry did it the boring way. It so often comes back to eating healthy, sensible portions, and exercise.

It’s not marketable, it’s not exciting, and it’s not inviting. But it works!

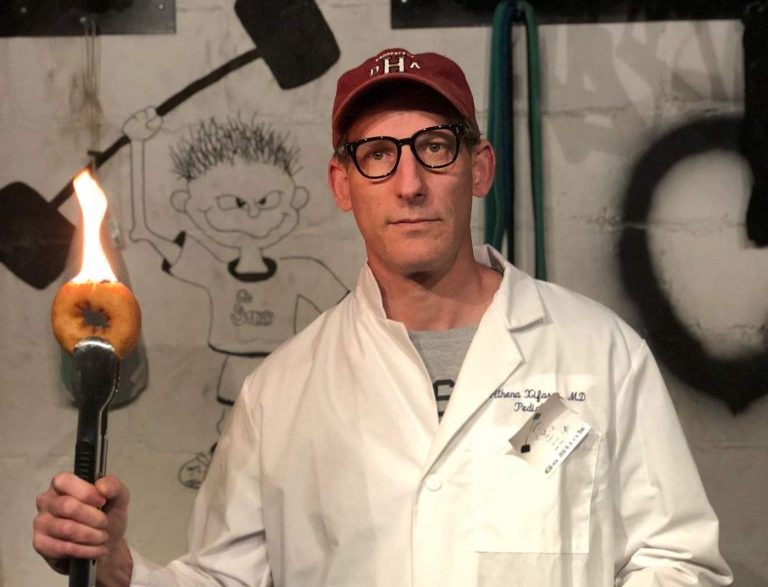

Norm Meltzer aka The Muscle-less Wonder